Emma Crawford is a recognizable name in the Pikes Peak region today. Since 1995, Manitou Springs has been holding the annual Emma Crawford Coffin Races and Parade. As one local website described it, “costumed impersonators of Emma Crawford, a 19th-century local who was buried on nearby Red Mountain, ride on coffin-like contraptions pulled by teams of four mourners. (Emma supposedly still haunts the mountain even though her coffin washed away years after her burial.) A parade and awards for the best Emma, the most creative coffin, and the best overall entourage complete the daylong event.” Despite the notoriety of Emma Crawford, her legend as the ghost of Red Mountain has overshadowed factual information about her life.

Emma Crawford was born on March 24, 1863, in South Royalston, Massachusetts. Musical at a very early age, Emma developed her talent with the help of her mother, Madame Jeanette Crawford, who was a pianist and music teacher. It is said that at the age of three, Emma “liked no plaything better than to sit on the piano cover and to listen to her mother practicing Beethoven’s sonatas.” At age twelve, she gave piano lessons and public recitals, and at age 15, was “able to render the music of the great masters with rare perfection,” playing the piano parts in a series of concerts given by a renowned violinist and a cellist in Boston in the winter of 1878. Emma favored Beethoven, Chopin, Schumann, and Wagner, and her playing style was “distinguished by a most delicate touch, a soulful expression, and a power which seemed almost incredible by hands so tender and delicate.” She also played the violin, viola, cello, and mandolin—instruments she mastered while taking rests from her piano work. Emma’s obituary in the Colorado City Iris would later report that she “is said to have acquired her remarkable masterly control of the piano from spirit instruction and is said to have never taken a lesson at mortal hands in her life.”

Emma, who been ill since age seven, moved with her mother from Massachusetts to Manitou around 1889, in the hope that the local mineral springs (from which the city took its name) and the mountain air might be a cure for her illness, presumed to be tuberculosis. This belief was not unusual at the time and many people suffering from the disease found their way to Manitou Springs.

Although not found in records such as city directories, longtime Manitou resident William “Bill” S. Crosby recounted in 1947 that Emma and her mother initially rented a two-story frame house with a gable roof and bay windows located on Capitol Hill. This house has been identified as 104 Capitol Hill Avenue. Emma ended up staying in Manitou in hopes of regaining her health in the fresh air and sunshine. She was reportedly engaged to a Mr. Wilhelm Hildenbrand, an engineer from New York who was said to be working on the Pikes Peak Cog Railroad.

It is said that next to music, nature was Emma’s second love, and she could be seen in a red dress climbing Red Mountain, which she nicknamed “Red Chief,” in honor of American Indians. A 1969 Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph article by Rufus Porter claims that the Crawfords were spiritualists, and like many spiritualists of the time period, believed they had “an Indian guide from the spirit world to protect them in the present one.” Many spiritualists of the time equated American Indian spirit guides with having a power to mend physical health. In the Porter article from 1969, the following anecdote is shared, more than likely coming from the 95-year-old Bill Crosby:

“One day Emma fancied she saw a handsome buck Indian beckoning to her from the top of Red Mountain. She vowed that she would climb the mountain and meet her Indian guide. Firm in her resolve, she revealed her plan to her mother and her lover. Both were opposed to such an ordeal for a girl in her delicate condition, as were all her friends and neighbors when they heard of it. But their pleadings were of no avail. She slipped off one day when her mother was teaching piano to a neighbor lady and climbed the mountain to the very top. She was very late getting back home, but no one would believe her when she told them where she had been. “I did so climb it,” she said, “and I tied my scarf to a little pinon pine tree on the summit, and I have decided that I will be buried beneath that tree.”

Crosby, a friend of Emma’s, reported that he climbed Red Mountain the following day and found Emma’s scarf tied to the tree, along with her footprints at the summit of Red Mountain that Emma wished to be buried, a request she is said to have made to a male friend (presumed to be Wilhelm Hildenbrand) while hiking on the mountain. Emma’s obituary reports that she “had a horror of cemeteries, formalities and anything low or gloomy, and even death, and wished to be carried high to sunshine and pure air.”

Emma’s death came on December 4, 1891 at 10:30 p.m. Her obituary remarked, “The few who knew her here remarked her calm, unruffled mood, and though her life was such that intimates were few, she was known by nearly all as a musician of rare power and skill.” The Manitou Springs Journal reported:

Upon the door of a cottage on Ute avenue then hung pendant, several days thereafter [Emma’s death], a white cape [sic], though she, whose departure was thus announced, had in this life passed beyond the bower where brook and river meet.

The funeral services were held at “the family residence on Ute Avenue” on Tuesday afternoon, December 8, 1891. That residence may have been 137 Ute Avenue where a City Directory some years later showed Emma’s Mother, sister Alice and niece Maurine boarding. Those who attended were “intimate friends and votaries of the faith to which the deceased was an adherent.” “Votaries of the faith” perhaps alluded to the Society of Progressive Spiritualists of Colorado Springs. Reverend A. R. Kieffer, rector of Grace Episcopal Church, led the service and “based his remarks on a beautiful poem.” The reverend had some affiliation with the spiritualist society, appearing as a guest lecturer for the group in 1893. The Manitou Springs Journal characterized the service as “unusual, but very impressive, and partook not of the customary sadness of such scenes.” Emma’s mother, Jeanette, performed a selection of piano pieces with “peculiarly sweet melody and weird harmony.”

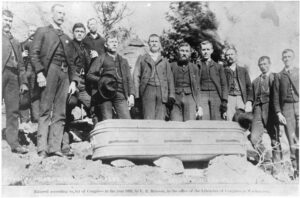

Crosby recalled that Emma’s fiancée, Wilhelm Hildenbrand, tried unsuccessfully to get a deed to the site for burial on the summit of Red Mountain. Her burial at that location, where “a beautiful view can be obtained”, however, proceeded. The gray casket with silver handles and silver engraved nameplate was reportedly carried to a hearse and driven up four blocks on Ruxton Avenue. Then, a group of twelve pallbearers worked in two shifts to transport Emma’s casket to the top of Red Mountain. H. H. Gosling, J. G. Hiestand, David Jones, Peter Mistler, and Howard Jones were names of some of pallbearers. Crosby, who was a teenager at the time, accompanied his grandfather, H. H. Gosling, to the burial and remembered, “They buried Emma on the mountain top, beneath an ugly wind-swept tree, and they covered the grave with rocks. Hildenbrand stood like a stricken man beside that grave. The mother and other mourners only went as far as the cañon.

Crosby recalled that Emma’s grave was moved over on the west side of Red Mountain, put into “loose gravel,” and covered with a concrete slab when the Red Mountain Incline erected a powerhouse and depot on the summit. Although Crosby recalled this event as happening in 1924, newspapers reported the construction of Red Mountain Incline occurring in 1912. On August 4, 1929, two boys found a human skull on Red Mountain and were questioned by police. Marshal David S. Banks of Manitou investigated and found wrapped in a bundle, human bones and the handle of a coffin at “the back of the Colorado house on Waltham Avenue.” The Colorado House (a boarding house) was located 397 Manitou Avenue (now 1143 Manitou Avenue) and the property extended between Manitou and Waltham Avenues. Given the proximity to Red Mountain, the remains would have been moved to Waltham from where they were originally found. A casket nameplate was also recovered which confirmed the remains were in fact those of Emma L. Crawford. The remains were brought to City Hall. In the issue of the reburial of Emma on Red Mountain, the El Paso County coroner, Dr. G. B. Gilmore, claimed that he had no jurisdiction in the matter, as outside of an incorporated town, as was Red Mountain, persons could bury their dead where they wished. The August 16, 1929, Gazette reported that a new grave for Emma Crawford would be dug in a Manitou cemetery.

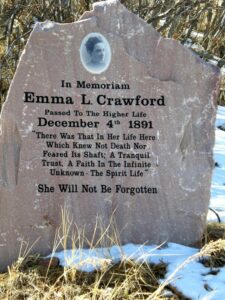

Emma’s restless remains stayed in storage for two years as the city tried in vain to find surviving relatives. Finally, one of her pallbearers, Bill Crosby, took responsibility for her remains and it was then she was interred at Crystal Valley Cemetery. Either way, she was buried in an unmarked grave. In 2004 (9 years after her memorial festival began) Historic Manitou Springs, Inc. provided Emma with a memorial stone in the approximate vicinity of where her bones were buried all those years ago. The Heritage Museum’s since wish was that Emma be honored her spirit rest in peace.

Learn more in our book called Emma Crawford – Her Life and Legacy. Get a copy online now.

References

- Peak Radar, “Emma Crawford Coffin Races and Parade” accessed June 16, 2012

- “To The Higher Life” Manitou Springs Journal, December 12, 1891, page 1.

- “Emma L. Crawford Obituary.” Colorado City Iris. December 12, 1891, page 8.

- O’Connor, Ellen. “Does Ghost Walk on Red Mountain? Old Tales Say So,” September 28, 1947, C:8.

- “Spirits Maintain Quiet Vigil,” Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph, October 27, 1984, F27

- “Dead Daughter Plays the Piano Says Madame,” Evening Edition Gazette. December 28, 1909, page 1.

- Porter, Rufus. “Long Ago, Two ‘Real Ghosts Visited Manitou…” Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph. October 25, 1969, p18C

- McGarry, Molly. Ghosts of Futures Past: Spiritualism and the Cultural Politics of Nineteenth Century. page 76

- Death announcement. Manitou Springs Journal. December 5, 1891, p. 2.

- 1892 Colorado Springs City Directory, p.159

- “Series of Lectures,” Colorado City Iris, March 18, 1893, p. 4.

- “Body Is That of Marion Crawford.” Gazette, August 6, 1929, p.2

- “Worked Started on New Road Up Red Mountain.” Gazette January 28, 1912. P. 12

- City Directory, 1929 and 1930

- “Make Identification of Bones in Manitou,” Gazette, August 7, 1929 p. 14

- “Manitou to Bury Emma Crawford in Town Cemetery Now.” Colorado Springs Gazette, August 16, 1929, p. 6